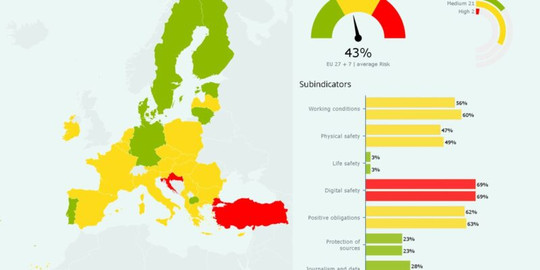

The “Media Pluralism Monitor” (MPM) shows that among the 32 European countries analysed, barely seven (Germany, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Finland and Lithuania) enjoy a satisfactory media pluralism situation. Everywhere else, European citizens are not fully guaranteed access to diversified and independent sources of information. Overall trends show increasing commercial and political interference in the media. The report also demonstrates the passivity of European governments and media companies in the face of this democratic threat.

The latest MPM report was released on 27 June by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF) and shows an overall deterioration in the situation of media pluralism across Europe.

The study assesses the risks to media pluralism in 32 European countries: 27 EU member states and 5 candidate countries (each country’s individual report can be accessed here). The report documents the health of media ecosystems, detailing threats to media pluralism and freedom. Results show that none of the countries analysed are free from attacks to media pluralism. Another alarming trend emerging from the report concerns editorial independence, which records a historic high-risk level this year. Commercial pressures compromise editorial independence, with media owners and advertisers influencing coverage.

Barely seven European countries have a satisfactory level of media pluralism. France is no longer one of Europe’s seven best performers. The countries with the highest rate of risk remain Turkey, Hungary, Albania, Serbia, Romania and Montenegro.

Poor safety protection. The safety of journalists, their working conditions and the legal threats they face are among the criteria examined. “Poor working conditions, attacks against journalists in the online environment, and governments not fulfilling their positive obligations towards the media, remain the most pressing issues”, says the report. In 2024, Turkey and Croatia remained as high-risk countries. Greece improved its ranking from being a high to medium-risk country. Only nine countries are in the low-risk band: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Portugal, Sweden, and the Republic of North Macedonia. Austria, Cyprus and, particularly, Slovakia moved from the low to the medium-risk band.

“With regard to Slovakia, among other reasons for this risk increase are the frequent attacks and intimidations suffered by journalists from different actors, including prominent politicians. For Latvia, even if the country remains in the medium-risk band, the risk increased significantly. This is mainly due to the constant threats and attacks directed against journalists, especially women, in the online environment, the absence of SLAPP monitoring, and the problems that arose when it was publicly discussed that a spyware program was found on journalists’ phones”, the report reads.

Journalists’ working conditions. Within the working conditions sub-indicator, like last year, only Denmark, Germany, Ireland and Sweden scored as low risk, while 13 of the 32 countries assessed scored as being at high risk (Albania, Austria, Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Montenegro, Romania, Serbia, the Czech Republic, the Republic of North Macedonia and Turkey). Among the countries that scored high risk, Croatia, Montenegro, and Romania scored 97%, which is the highest possible level of risk used in the MPM methodology. The report says that “it is worth noting the very high number of high-risk countries for this sub-indicator, when compared to the other questions under analysis in the MPM”.

“Particularly difficult working conditions are faced by local and regional journalists, receiving lower salaries and more fragile or absent social security schemes, as reported in virtually all the Member States and candidate countries in MPM2024, and by the Local Media for Democracy study. A more precarious situation is also faced by freelancers and young journalists. In France, unions have denounced the “uberization” of young journalists, and media outlets resorting to the multiplication of short-term contracts, self-employment, payment in author rights, internships. In addition, journalistic organisations are not always effective in defending the rights of the profession: in particular, the low popularity of journalistic associations in post-communist EU Member States and candidate countries makes bargaining for better working conditions more difficult. Institutions are also not active in addressing the precariousness of the profession: in Italy, for example, the expiration of the primary collective contract for journalists (FIEG-FNSI) in 2016, yet to be renewed, underscores institutional neglect. As highlighted in the Italian report, these circumstances heighten journalists’ vulnerability to external influences such as commercial or political pressures, particularly in the absence of robust safeguards and certainty”.

Physical safety. Physical safety is another sub-indicator that is fundamental to the evaluation of preconditions for free journalism. In MPM2024, eight countries (three more than last year) scored as being at high risk: Bulgaria, France, Greece, Poland, Spain, Serbia, the Netherlands, and Turkey. Attacks and intimidation sometimes come from top level politicians: in Slovakia, for example, the risk score for this sub-indicator significantly increased this year (moving from low to medium-risk), given a continuous trend of this kind of intimidations. In November 2023, Prime Minister Robert Fico attacked four major media outlets labelling them as enemies and hostile media. In Latvia, “journalists have regularly admitted in public interviews that certain politicians attempted regular attacks on journalists by perceiving that during the war [in Ukraine], professional journalism shall represent the state’s and/or actual political position, rather than trying to provide professional content and diversity of opinions. These attacks by politicians and politically involved users of social networking platforms have created risks of self-censorship, increased hatred against journalists, and harmed the diversity of content”.

Digital safety. Specific threats occurring in the online environment, including those that appear through the illegitimate surveillance of journalists’ searches and online activities, their email or social media profiles, hacking and other attacks by state or non-state actors, are discussed under the sub-indicator Digital safety. The report shows that half of the countries under study scored a high risk in this regard.

Recommendations. In its conclusions, the MPM report calls on the states and public authorities:

- to improve the working conditions of journalists by the adoption of legal frameworks that allow for better labour conditions in the sector. This would include extending the public social protection schemes to all persons who practise professional journalism (whether they are regularly employed or freelancers) and incentivising collective bargaining to introduce new kinds of economic protection against market downturns.

- to promote the safety of journalists by raising awareness among state institutions (e.g., the judiciary and the police) about the importance of the media for democracy, and by avoiding unjustified arrests and impunity for crimes that are linked to journalism.

- to encourage collaboration between the state and the media in ensuring the safety of journalists, e.g., to organise training on how to behave while covering protests or other high-risk events; to encourage journalists to denounce the intimidation and attacks received as a consequence of their job; to set systematic monitoring systems of SLAPPs and other forms of attacks against journalists, with particular attention to the gender dimension of these threats.

- to condemn the political elite’s attacks on journalists.

- to implement the European Commission’s Recommendation “on ensuring the protection, safety and empowerment of journalists and other media professionals in the European Union”.

- to promote the implementation of an effective anti-SLAPP legal framework that is able to prevent arbitrary and unlawful attempts to silence legitimate professional journalistic and civil society activities, including allowing judges to expeditiously dismiss unfounded lawsuits that are brought against journalists and human rights defenders. The principles and practices enshrined in the 2024 EU anti-SLAPP directive for cross-border vexatious lawsuits and in the Council of Europe’s Recommendation CM/Rec(2024)2 “on countering the use of strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs)” should be taken into utmost account also in the internal legal order.

- to avoid the use of spyware and other intrusive surveillance technologies on journalists and other public watchdogs, even beyond the limitations set by Art. 4 of the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA).

The report also calls on media companies “to ensure decent working conditions for their employees, e.g. avoid forcing journalists to become self-employed even though the nature of their collaboration mimics standard full-time employment contracts”.

“In ten years of implementing the Media Pluralism Monitor, we have observed the emergence of many new challenges in parallel with the digital transformation. Today, more than ever, there is a dire need to support journalism and media pluralism. We look forward to assessing the effects of the European Media Freedom Act in the Member States and call on governments to commit to protecting press freedom as a pillar of our democracy,” said Pier Luigi Parcu, Director of the CMPF.

“It is despairing to note that the situation of media pluralism is deteriorating year after year without most European governments or media companies taking the necessary measures to halt this deterioration,” said EFJ President Maja Sever. “The EFJ has been calling for these measures for years. The MPM report has the advantage of pointing the finger at those responsible for this passivity: what are the public authorities waiting for to preserve the right of citizens to access independent and pluralistic information? We will continue to denounce in the strongest possible terms those political decision-makers who act as the gravediggers of press freedom, whether actively or through their culpable passivity”.

IFJ President Dominique Pradalié said: "A free and independent press is a sign of good democracy and we must take a firm stand in the face of the MPM's worrying results. Unions have a crucial role to play in upholding media independence principles and must be considered as core partners for addressing the pluralism deficit in Europan media. In times where democracy is particularly at stake, citizens need a free press and governments must to their utmost to guarantee media diversity. Time for change. "