I have been told by more than one person that being a member, and especially serving on the board, of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) is part of the reason why I keep being red-tagged.

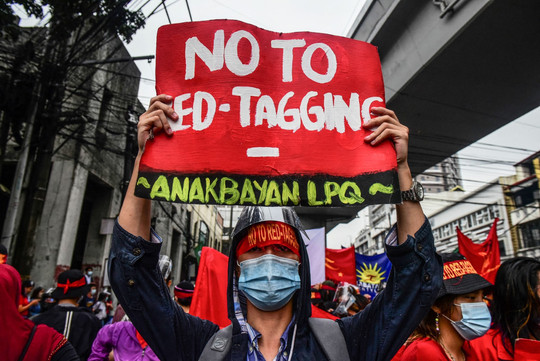

Red-tagging is a longtime practice in the Philippines - the title holder for Asia’s longest-running communist insurgency - where people critical of the government are labelled communists. While red-tagging has been a harmful practice since the time of the Marcos Sr dictatorship, it became more dangerous in the Rodrigo Duterte government because of the newly passed anti-terror law, under which they designated exiled communist leaders, and consultants of the peace talks, as terrorists. Designation is a new power under the 2020 anti-terror law, in which a group of non-elected executive officials can arbitrarily ‘tag’ anyone as a terrorist in secret hearings, without notice to the subject until they are publicly named.

The NUJP is the biggest and broadest lateral guild of Filipino journalists, with 30 chapters across different news organizations, including Filipino freelancers in the country and across the world. The NUJP was established in 1986 to respond to the press censorship done by former dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. NUJP is as old (or as young) as the Philippines' fragile democracy, and we’ve continued to be progressive in our ways.

Among our projects is providing support to persecuted journalists. We also have a safety office monitoring all kinds of attacks against the press - whether that’s online, or physical. It goes without saying that we are a press guild critical of the government. Red-tagging is a natural consequence of being one, and former Duterte officials would brazenly tag NUJP officers in livestreamed press conferences as high-ranking officials of the Communist Party.

After I interviewed then-incoming Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin “Boying” Remulla, where I asked him about the dangers of red-tagging, TikTok pages made a reel of myself in that interview, colouring it red and putting the following text in spooky font: “Lian Buan - CTG spox??” meaning Communist Terrorist Group spokesperson.

People - activists, and other community organizers - who have been red-tagged have been killed: human rights defender Zara Alvarez, labour leader Manny Asuncion and unionist Dandy Miguel, to name a few. Journalists who were red-tagged have been jailed - Manila Today editor Lady Ann Salem, Paghimutad correspondent Anne Krueger, and student radio broadcaster Frenchie Mae Cumpio, who has been detained for over 4 years now.

It’s a system designed to target dissenters. When a dissenter is labelled as red or a communist, it undermines due process because the State can find a shortcut to arrest red-tagged people without arrest warrants, as in the case of Salem and Cumpio, and charge them with flimsy cases of illegal possession of firearms and explosives, the common charge against activists. Salem has now been cleared of all charges after a victory in an appellate court finding a search warrant against her was invalid from the start, upholding the case’s dismissal in September 2023. Activists claim that during Duterte’s term, state agents planted firearms and explosives during their raids. The Supreme Court has since removed the power of judges from Metro Manila to issue search warrants outside their jurisdictions.

Red-tagging

NUJP decided to conduct a study on red-tagging because the government keeps claiming that either it does not exist as a practice, or that the State is not behind it. Even President Ferdinand Marcos Jr, who has attempted to project a human rights focus in his and his cabinet’s presentations internationally, said that “the government does not do” red-tagging.

Sometimes, the strategy is a divide and conquer messaging: if you don’t ally with the alternative press, or if you don’t cover the human rights groups, then you have nothing to worry about.

What we found in our study,‘NO TAG: Press Freedom for Pluralism’, proves this premise is fundamentally wrong: 60 per cent of the red-tagging attacks against journalists have been state-sponsored, 19.8 per cent were done directly by the state through the most intimidating method of police visits to a journalist’s home, or sending a letter using official letterheads. Of the surveyed attacks, 43.4 per cent were victims coming from mainstream news organisations, which is not significantly disproportionate to the 56.6 per cent of victims from the alternative press.

Some journalists reported being red-tagged after simply doing political stories critical of Duterte or Marcos, and that those attacks were amplified by pro-Duterte or pro-Marcos accounts.

Using methods of survey and focus group discussions (FGDs), we found that red-tagging has gone beyond counterinsurgency efforts, to an all-encompassing tool to intimidate critical journalists, or at the very least, to tire them out.

Accountability

What prompted the study was also frustration with the accountability mechanisms. In countless fora on red-tagging, government officials from the justice sector always advise availing of the remedies of amparo and habeas data. The writ of amparo (Latin word for protection) is a Philippine judicial innovation that works as a restraining order (because we don’t have restraining orders in the Philippines). Habeas Data (Latin phrase for “you have the data”) compels people to destroy the data. In the red-tagging context, the subject of the writ will have to remove the names of the victims in their list - oftentimes referred to as the order of battle or OB, the longtime nomenclature of the Philippine military for their counterinsurgency targets.

But there is a long track record of activists and journalists failing to get the amparo and/or habeas data. This has already prompted a campaign during the pandemic to review the strengths of those writs - which the Supreme Court already promised they would do.

Worse, there is no law criminalizing or even defining red-tagging. A criminal law would have free speech implications that even red-tagging victims would be uncomfortable with. It’s this discomfort that stops victims from filing criminal libel, or any other criminal offences, against their red-taggers. Journalist Atom Araullo resorted to civil suits.

Even the Supreme Court’s contempt ruling against notorious red-tagger Lorraine Badoy, a former Palace press official under Duterte, did not discuss red-tagging even though the root of the court’s motu-proprio investigation into her was her act of red-tagging a judge.

We made headway when, on May 8 this year, the Supreme Court publicized an Amparo grant to former lawmaker and longtime activist Siegfred Deduro. In granting Deduro the writ of amparo, the Supreme Court finally defined red-tagging as a “threat to a person’s

right to life, liberty, or security” and “a likely precursor to abduction or extrajudicial killing.” The Supreme Court also said that red-tagging may be perpetrated by “vigilantes, paramilitary groups, or even State agents.”

But even so, not every journalist has the resources to file a case or request the court for a writ. That requires financial resources that journalists, or even their newsrooms, do not have.

We are a country still plagued by rampant contractualisation of the press, where provincial correspondents are paid as low as USD85 per month. Only 25 per cent of red-tagged journalists filed a suit or a report, mostly with the independent Commission on Human Rights (CHR). To date, no red-tagged journalists have secured any kind of judicial or quasi-judicial remedy.

Our study also found that news organizations took concrete action in only 3.7 per cent of the cases, such as offering the reporter to take a leave, changing assignments or providing security protocol. In a majority, or 70 per cent of the cases, newsroom actions were limited to releasing a statement of support for their red-tagged journalist, publishing a story, or asking how they are. “I hope newsrooms investigate red-tagging more clearly. But I hope the framework used for the investigation is how to protect the employee, how to protect the journalist, and not primarily how to protect the company,” said Rowena Paraan, formerly head of ABS-CBN’s citizen journalism arm and now training director for the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism.

Mental health impacts

The mental health impacts of red-tagging often go undiscussed. Filipino journalists generally do not like to appear weak, and covering dangerous stories is a badge of honour. Even at a time when mental health is already a mainstream topic and less taboo, our FGDs reveal that there is no robust mechanism to address the psychological impacts of red-tagging.

Local correspondent Jazmin Bonifacio would sleep under her bed for fear of strafing. Inday Espina Varona, whose last role before retirement was Rappler’s regional head, would “peek at my door every time there’s rustling at night.” Janess Ellao of Bulatlat would not sleep until 5:00 am during the time that search warrants were being served left-and-right to activists - usually before sunrise.

Red-tagged journalists have implemented personal safety protocols: they changed their names in ride-hailing apps, or home shopping apps, and for some, spent less time with their families to spare them from surveillance. “That’s just not a healthy way to live. It was a general pervading heavy weight on your shoulders,” said Varona.

The way forward

The recent Supreme Court decision defining red-tagging is a positive step forward. But having covered the justice system, I maintain a healthy dose of pessimism. Besides, when the Supreme Court created the writs of amparo and habeas data in 2007 to address the alarming rise in enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings, it was also hailed as a game-changer for human rights. The game did not change, as we are experiencing it today.

I don’t subscribe to the notion that justice is apolitical. Everything is political. Marcos Jr is now projecting himself on the international scene as a human rights ally. His motivations can be speculated by anyone. What is certain is that this provides momentum for the human rights movement to call his deal. The CHR, for example, is an independent organ created by the 1987 ‘revolutionary’ constitution as an answer to the abuses of the dictatorship of his father. A weakened CHR under Marcos Jr would be a blow to his global projection of being a democratic leader who wants to be “judged not by my ancestors, but my own actions.”

That said, the CHR can establish a system against red-tagging and protect those victimized by it. The CHR has stood firm against red-tagging and launched a Viber group where red-tagging can be reported in real time, but these seem to be all reactive rather than preventive.

There is momentum under Marcos Jr to push all human rights mechanisms to their maximum capabilities. Marcos Jr also wants to differentiate himself from his predecessor Duterte, and the recent breakup of the Marcos-Duterte alliance provides a rare alignment of political stars to push the human rights agenda.

But so far, Marcos Jr has refused to abolish the red-tagging National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC), a Duterte-time task force responsible for many of the blatant red-tagging incidents. Marcos Jr has also refused to acknowledge that red-tagging is state-sponsored.

Irene Khan, United Nations Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression, is right. The Philippines is vying for a United Nations Security Council membership, and these demands to end red-tagging can be leveraged for his government to secure what they want out of the UN.

We hope the international community can help sustain this pressure.

As for me, if I quit the NUJP - which stood by me as a young producer suing a giant network for labour violations, and which stands by many journalists for all their woes and challenges - because I am scared of being red-tagged, then I would have allowed my attackers to win. As mentioned earlier, the goal is to exhaust you, to tire you out, and to make you retreat. Standing firm with the union is my biggest weapon.

Lian Buan is the lead author of the latest NUJP report on red-tagging, 'No-Tag: Press Freedom for Pluralism'. She was a director of the Union from 2020-2024, and helped establish the NUJP local chapter in Rappler, where she is a senior investigative reporter.